![]()

Watch and listen to the sermon on Facebook:

![]()

I cannot, in good conscience, offer you this sermon today without pointing out that I am a white woman in 2017 speaking to you about the lived experience of a Black woman in 1946. I am claiming her story in the fulfillment of my work, using it for my own ends. No matter how well-researched, or how well-intentioned, my sermon is, I am still a white woman interpreting and retelling the personal experience of a Black woman. That fact will be hurtful to some, possibly many. Possibly even in this room right now. Impact always outweighs intent.

And, at the same time, it is the very least I can do as an ally to indigenous peoples and people of colour (two identities between which there is much overlap), it is the very least I can do to use my power and privilege as minister of this congregation to share this story. To be intentional with our full worship team about lifting up the voices of those who have been marginalized and oppressed.

In preaching about Viola Desmond this morning I am trying to dismantle systemic racism while at the same time continuing to participate in it. It is a complicated question that does not have a one-size-fits-all answer, and it relies on both things being true in order to be authentic.

I’ve been a runner for a few years now, and one of the things that happens is you find yourself part of the online running community. Groups where people share stories, tips, and generally support each other. One of the things that was given to me by a member of the online running community was when a Black man shared with us what he has to do to stay alive as a Black man running in the streets of his home.

He always, always, without fail, wears the brightest, most neon clothing he can find — from the sweatband on his head all the way down to his toes. He puts on reflective gear, so that headlights will make him known in the dark and the attempt to be visible can be recognized even in the daytime. He wants to be seen, so that no one can argue he was trying to hide or look inconspicuous. He always wears a shirt from a race he’s done in the past, so that on first look people can get that extra piece of information before judging him. He does all of this, because in his experience when people in our dominant culture see a Black man running, they assume he’s running away from the scene of a crime, and to protect his life he has to make them think something different.

That is not my experience as a runner. It never has been, and it never will be. And I think that everyone here, regardless of how you have been racialized in your identity, can agree that it would be preposterous to argue that because my experience was different, that therefore his isn’t true. And yet, this is what happens every single day to people of colour, both inside and outside this congregation. The pervasive abuses of systemic racism that continue in our modern, dominant culture are not hearsay to be debated. They are documented fact. Here is just one: in Policing Black Lives, Robin Maynard says:

“Black communities live in a state of heightened anxiety surrounding the possibility of bodily harm in the name of law enforcement. A genuine fear of law enforcement officers exists among many in the Black community, a response that is rational given the circumstances. In a society where many white Canadians think of the police as those who protect their security, Black people, quite legitimately, largely fear for their for their security in any situation that could involve the police. Parents, in particular, have expressed a genuine concern for the physical safety of their loved ones.” (Maynard 102)

“Though police killings, like other forms of systemic racism, are frequently justified by invoking Black criminality and “dangerousness,” this does not stand up to scrutiny. Criminal involvement does not, by any means, provide moral justification for police killings. However, police use of force also does not correlate to rates of Black criminality: while most white persons involved in incidents of police use of force have criminal records, this is not the case for Black Canadians. Instead, it is race that impacts police treatment: in one study, it was discovered that when responding to “minor offences,” police drew their weapons during arrest four times more often when arresting Blacks than any other group. Black people continue to be killed by police in situations that could have been de-escalated by other means and often due to police interventions that would not have even occurred had they been white. (Maynard 107)

We have covenanted together to affirm and promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person. That is not the same as the inherent worth and dignity of every opinion. Anyone, and I do mean anyone, is welcome to join us in this community, but to stay they must be willing to do the work of examining their sustaining beliefs, and their choices in the world. When we fail to hold people accountable for their beliefs that lead to the destruction of those that are not like them, we are failing our core Unitarian Universalist principles. White supremacists will not find a home here. Neo-Nazis will not find a home here.

Making room for everyone does not mean that we ignore those who are using that room to hurt others. Being freethinkers doesn’t mean that we are free to use oppressive language and to choose oppressive actions. Freedom from dogma and creeds does not mean freedom from ethical accountability. None of us can claim to be living into our full potential, or claim to be nourishing our spirit, when we are at the same time ignoring We can and should be better than this — not only to truly honour the diversity we have among us today, but to ensure a better future for those who will come after us.

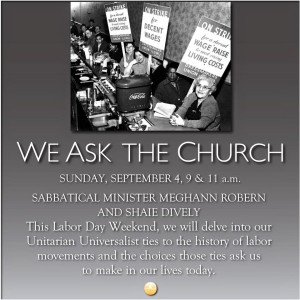

Our choir today, singing the words of Unitarian Universalist Dr. Ysaye Barwell, asks if any of us would harbour, or maybe even become, a Harriett Tubman or Sojourner Truth, those fierce women of colour in the fight against slavery in North America. Would any of us harbour, or maybe even become, a Thomas Garrett, a white Quaker who helped innumerable Black people escape slavery on the Underground Railroad. This is a question for everyone here, because systemic racism poisons all of us. Viola’s sister, Wanda, describes how many people of colour expend great effort to stay out of trouble, to stay under the radar, because of the danger of being noticed.

She herself describes how she was aware of her Blackness by the time she was in junior high, and that she was ashamed of her sister for getting arrested. Viola, who only wanted to be able to see a movie in focus, and tried to pay for the proper ticket, and was forcibly dragged out of the theatre by two men as she clawed at her surroundings. Her own sister was cultured to be ashamed of rising up to defend oneself against racism. Even now, when people of colour protest peacefully, pay attention to how they are described by the dominant media — uppity. “Doing it wrong” “An inconvenience.” That is a legacy of a culture in which slaves ought to know their place.

And I know, I know, some of you are right now squirming in your seats and figuring out how to tell me after the service that sermons should be about the spiritual, that this is too political. Well, this is spiritual work. Viola Desmond is going to be the face of our new $10 bill. And yet, still, in 2017 people are dying because of the colour of their skin, and they are crying out for help, and they are being ignored because the majority of our culture can’t handle multiple experiences of the same thing. Because it is, spiritually, mentally, emotionally, incredibly hard to do so.

Why? Because the story we tell of our individual life, the narrative sum of our experiences, is the definition of who we are. Being able to form a coherent self-narrative is one of the ways we heal from traumatic events. So when we are asked to validate a different narrative, one that often contradicts our own, it feels threatening. It feels like an attempt to erase us. So we get defensive. This is spiritual work, because it affects our spirit, the stuff that makes each of us, us.

And when we feel threatened, when we feel defensive, we often forget to take into account the bigger picture — which includes a power analysis. When two individual accounts of reality conflict, and those involved will only allow one to be “The Truth,” then the one that has more power will win. Remember the saying, history is written by the winners? And one wins in a conflict by having more power — more money, more resources, the “right” assigned sex, the “right” size body, the “normal” skin colour. And here’s the other thing that’s so hard for us to understand, because it cuts right to how we define ourselves — it’s possible to have privilege and not have privilege at the same time.

I have immense privilege as a white person. I am marginalized as a woman. I have privilege of class, due to the pure luck of my birth. I am marginalized as a queer person. I have privilege due to my level of education — which is also linked to my whiteness and my class status — and I am marginalized due to my size. Holding different experiences of the same thing in tension with each other means that someone else having life struggles doesn’t diminish my own — but if I am going to be a true partner, if I am going to truly live into our shared UU principles and shared values, I have to acknowledge multiple realities as true. I have suffered immense pain in my life due to my size.

When I go running, I have to keep eye out for people throwing things at me because they think it’s funny to see a fat woman running. I’ve had horrible things shouted at me, been called awful names. But never, not once, have I been afraid for my life. My suffering is not negated by my fellow runner’s suffering as a Black man, and I can hold my painful experience as valid while also naming that his has been much worse. The real question is — how can we help each other find freedom in this world by changing it for the better? This is what it means to be intersectional.

Each situation, each choice, must be examined, must be held accountable to the larger work of dismantling systemic racism (and classism, and sexism, and ableism, and, and, and). And, I firmly believe that if there is a religion in the human experience that is capable of living into that tension, of holding multiple truths in a loving embrace and asking what’s next — it is Unitarian Universalism. We have failed at this many many times. But the promise, the potential of world-changing healing is there… if we are willing to take certain risks. But the how and when of those risks will be distinctly different depending on our racial and other social identities.

Those of us who are white will be asked to do very different things than those of us who are indigenous people and people of colour. Those of us who are white will need to always remember that we can go places, do things, say things that people of colour cannot without risking life and limb, much less freedom. White people are less likely to die in jail, or even die during arrest. And for those of us who are people of colour — the white people, myself included, are going to mess up. White people are going to continue to say awful things and make bad assumptions and forget to decenter themselves and their whiteness as they do this work of breaking down these systems and I’m so very sorry it won’t change overnight. But as I said to you a couple of weeks ago…. Perfect is the enemy of good. Perfect is the enemy of better. We can’t wait until we’re perfect to do the work. None of us will survive that long.

We Unitarian Universalists are a covenantal people, no matter what our colour. We are bound together by the promises we make to each other about how we are going to build and sustain this community, about how we are going to teach the larger world what it means to believe different things but to still care about each other. The seeds are already within us, within this community. This is spiritual work, for the betterment of all. As we go forth today, remember — there is more love somewhere. There is always more love somewhere. And we’re gonna find it. Together.

May it be so.

![]()