Watch and listen to the sermon on Facebook

The Book of Revelation. It’s a letter written by a person who called themselves John, meant for seven communities in Asia that had gathered around a belief in Jesus Christ. Unlike today, when Christian identity is linked with power and empire, Christian communities (even before they were calling themselves Christians) were subversive, anti-establishment groups fighting just to survive, much less thrive. Living in the shadow of the Roman Empire, which required imperial religious devotion in all aspects of life, including commerce and livelihood, many resorted to hiding in plain sight. They kept their beliefs about Jesus internal, while their actions supported the divinity of the Roman emperor and his authority over all because it kept them alive.

Enter John, the Revelator. Not the same John to whom the fourth Gospel is attributed, or the Johannine letters. A different John. He’s a Palestinian Jew, living among the Jesus communities in Asia, and he is so angry at his people for their collaboration with the empire that persecutes them, and so afraid that the message of Jesus, his messiah, will be erased, that he cannot truly express how he feels in everyday, conversational language. He is so overwhelmed he cannot even rely on traditional rhetoric like what Paul used in his letters. John can only communicate the depth and agony of his truth through manifesting visceral gut reactions to his fantastical and often grotesque imagery. The four horsemen of the apocalypse. The beast rising from the sea. The dragon sweeping stars from the sky with a flick of its tail. The woman clothed in the sun, with the moon at her feet.

The imagery of John’s epistle is so powerful it has moved past Christian culture and entered the consciousness of the American secular experience. It’s the basis of numerous pop culture endeavors, like television shows, and referenced in many more. I would argue that it’s used as a founding cosmology in the creation of our art more than it’s used as a Christian sacred texts in modern churches. Many mainline Christian pastors are afraid of trying to exegete it, like English majors tiptoeing around James Joyce’s Ulysses. It’s powerful at an emotional, reactive level. And one of the hardest things to deal with about Revelation is its violence.

Miroslav Wolf, a Bible scholar and survivor of the genocide in the Balkan peninsula claims that: “In the worldview of Revelation, there is no power great enough to stop the beasts from wanting to be beasts.” There is no power great enough to stop the beasts from wanting to be beasts. What do we do with that as Unitarian Universalists?

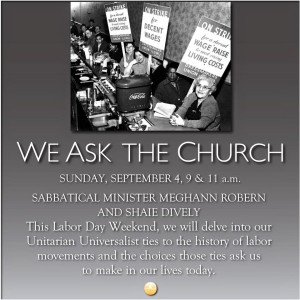

I think we have to go back to King, the authentic King, the one who understood that non-violent action does not mean it is not disruptive. Non-violent action, civil disobedience, must be disruptive, must make Rome agitate, for it have any effect. But King’s call to non-violence is also deeply rooted in Universalism, in demonstrating that those who hold the power in an oppressive system are just as much victims of that toxic environment as those who are oppressed. That we are called to love even the beasts who want to be beasts. That love is how we show beasts that they do not have to be beasts to belong. As UU Rev. Anita Farber-Robertson says: “My Universalism is fierce. It has no patience with a theology of scarcity.”

King also lays out for us a historical record of what he calls “creative extremists”. And it’s important to note that these leaders of change were not themselves perfect, nor were their messages always perfect. John’s resistance to religious imperialism did not intersect with resistance to patriarchy — his fantastical visions rely on caricatures of the historically oppressive roles of women — mother or whore. Thomas Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal” but left out the white women, the black lives that kept his household, and the economy of the Southern United States, running on slavery of human beings. That historical erasure of the humanity of black lives affected all people of colour as this nation formed its identity. It’s a legacy with which we are all still struggling today. Revelation is resistance.

To resist, we must acknowledge that our pasts are imperfect, and we are imperfect, and that’s okay as long as we are willing to keep learning. It is incumbent on us to learn from the mistakes and misunderstandings of our histories so that we can always be evolving into the people the visionary future needs to create itself. We will always be imperfect, because we will always be creating something new. We make each other better by learning from each other and the diversity of our experiences and our belief. We covenant together to more than the sum of our parts in building the future.

Revelation is resistance to the status quo. Revelation asks us to consider how we navigate questions of fidelity to covenanted communities of mutual love and support, leading to action on justice issues, when we live in a culture that demands unquestioning fidelity to imperial projects. In modern times, that becomes how do we navigate a covenanted agreement to make our seven principles, statements of hope and vision, the reality in this world that demands we agree to private prison industrial complex, the oppression of black lives, Muslim lives, Latinx lives, queer lives, and so many more. There are, right now, thousands of people supporting the First Nations protests of the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, protesting for the sake of the future of clean water for our children and grandchildren. Those thousands of people are being ignored by the mainstream media while they report about a gas panic due to — wait for it — a broken gas pipeline polluting everything around it. The cognitive dissonance is staggering. Revelation 13:4: “They worshipped the dragon, for he had given his authority to the beast, and they worshipped the beast, saying, “Who is like the beast, and who can fight against it?”

We are, all of us, under the thumb of New Rome, my beloveds. And Revelation is resistance. Our seven principles are resistance.

I’m a huge fan of Nadia Bolz-Weber. She’s a Lutheran pastor who also happens to write some really good books. And it turns out that once upon a time, she tried to be a Unitarian Universalist. She decided it wasn’t for her because, for her, we UUs “have a higher opinion of human beings than I have ever felt comfortable claiming, as someone who both reads the paper and knows the condition of my own heart.” She claims that we rely too much on “hopefulness and positive thinking.” And this not a claim unique to her.

I offer to you today that we should not ignore or dismiss such judgements about us, but rather use them to fuel our drive to make our vision reality. I am willing to claim that hopefulness and positive thinking are central to our Unitarian Universalist identities, but they are not how we get things done. The hope is why we work for a better world. Love is why we work for a better world. The how is always changing. Revelation is resistance.

Our seven principles are not belief statements. They are statements of vision and mission around which we, as members and congregations, covenant to preserve where they exist and to make a reality where they are not. It is often very, very hard work, and more about confronting our own flaws of perception than is it about our own “awesomeness”.

Take, for example, our first principle: we covenant together to affirm and promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person. From a belief standpoint, we can recognize all around us, every day, how people are not shown, nor demonstrate, inherent worth and dignity. The difference, however, is that as UUs we are also willing to learn about, and then recognize, the systems of oppression that teach people to fear and hate each other. And, as we learned from the trolls in Frozen, “people make bad choices when they’re mad or scared or stressed.” When the systems keep people from having access to food, to shelter, to health care, they live in fear, and they make choices based on fear. I’m not sure those decisions can be called choices at all.

The covenant of our seven principles is about recognizing the divinity of others. And only when we have done that can we truly recognize the divinity in ourselves. That we are worthy of love simply because we exist. That each of us is enough, just as we are. That living into the worth and dignity of every person includes living into the fullness of our own individual potential as we help others live into theirs. Revelation is resistance, resistance to the old order, resistance to the empire, resistance to systems of oppression that harm all of us with their poisonous ways.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous image of the moral arc of the universe bending towards justice is, in fact, paraphrased from the writings of Unitarian Theodore Parker. King understood that that moral arc bends towards justice because people bend it. That moral arc requires our thoughts and prayers and our actions. And this community is a perfect example of how necessary a faith in hopefulness and positive thinking is to how we hold together as a congregation, as a larger denomination, despite our multitude of differences. Our sources of faith are numerous, but we share a vision that we can make people’s lives better, including our own; that we can ease suffering, including our own. That vision relies on our covenant to work, to love, together. Our differences make us stronger because they encourage us to learn from each other.

The Book of Revelation shows us a world of anger and fear, where violence is inevitable and divine retribution is the only escape into New Jerusalem, into the new world order. And if all we do is wait for someone better than us to change it, that’s what the world is and will continue to be. Because there is no one better than you, right here, right now, as part of this community. There is no one better to change the world.

In the words of Black Elk, sung by our choir today, “I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all children.”

We are the revelators. We are the creative extremists that King said the world needs.

Throw off the fear. Throw off the hate. Bring on the New Jerusalem.

Revelation is resistance.

May it be so.