Listen to the homily here:

Or, watch and listen to the homily on Facebook

I spent this summer working as a chaplain at Vanderbilt. And one of the most heartbreaking encounters I had was with a person I’ll call Alex.

Alex had been admitted for observation, as they had a lot of medical problems with as yet no concrete source. And without knowing why Alex was suffering so much, the doctors couldn’t treat them. And over the course of my many conversations with Alex, they confided in me, through uncontrollable tears, that they believed their physical suffering was a punishment from God.

I’m sure you can imagine what my gut reaction to that was. But my job as a chaplain was to listen, to help a person through their own theology, not to convert them to mine. So I asked Alex to tell me why they believe that.

“I’ve done awful things in my past,” they said. “I used to sell my body, as a prostitute. I did drugs. I was so sinful. And then one day, one of my clients, told me they loved me and wanted to marry me. They brought me to Jesus. They saved my life.”

Knowing that they would be admitted to the hospital for several days, Alex had brought comforting mementos. Their partner had died, but Alex showed me their love letters and wedding photographs. They played me voicemails from church members that they’d saved, messages of love and support. And the tears just kept flowing, because of that unspeakable thought that God is punishing them for past transgressions.

By all accounts, Alex’s conversion was genuine. Their participation in church life after the death of their partner was very clear, and that community knew their life story and welcomed them wholeheartedly. This sense of punishment was not coming from the people who had taught them religion.

So I nudged a little bit, asking them to think about the contradiction between how they describe the forgiveness freely given to them by their partner and their church, the forgiveness they clearly believed Jesus had given them, and this plague on their body they also feel was sent by God.

“I know Jesus loves me, and has forgiven me,” Alex said. “I know my love and my church has forgiven me, truly. <beat> I just can’t forgive myself.”

And there it is. That immense power that each of us has within us to define our reality. For better or for worse.

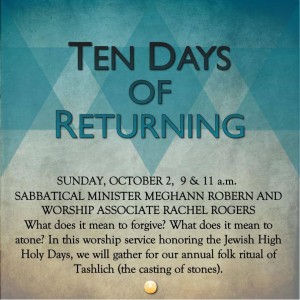

Tonight at sundown is the beginning of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year and the entrance to the Ten Days of Teshuvah. Now, in our Western culture, teshuvah is often translated as “repentance”.

Using repentance, on its own, is not a bad thing — it’s about recognizing one’s faults and committing to improving our behavior when we’ve done wrong. In our faith that is built on covenants, on making promises to one another about how we will be with each other in community, it’s important to be able to change for the better.

But repentance has a lot of emotional baggage that comes with it as a word in our culture. Sadness. Remorse. Even shame. There is the implication that when one repents, those parts of one’s life are erased, forgotten, or at least that they should be. That is where Alex was living. The other people in their life, the ones who taught them about love and forgiveness, were recognizing their whole self. They saw Alex’s past as an integral part of who they are, as part of the entire life that led them to be a loving partner and devoted member of a community spreading love and generosity in the world.

But Alex can’t escape the thought that they needed to be perfect all along. That to be worthy of that love and acceptance, that they need to somehow purge these experiences that have helped to make them who they are today. Alex is fighting being made whole in love.

According to many Jewish linguists, a more accurate translation of teshuvah for Western culture is “returning”. Not only does it carry less baggage than “repentance”, but it implies a cyclical, ongoing process around a centering point. Instead of a cutting off from the the past, teshuvah becomes about integration, and wholeness. In order to truly live out our full potential as human beings, we must be willing to recognize all of our past as part of our selves.

I talk a lot about how our Universalist heritage calls us to radical hospitality and loving those who we want to hate, usually in the context of others. Today, that radical hospitality and reaching out in love is for ourselves. These ten days of teshuvah, of returning, are an opportunity for us to say “I am loved. All of me.” All the forgiveness in the world from others means nothing if we’re not willing to forgive ourselves.