Listen to the sermon here:

Or, watch and listen to the sermon on Facebook

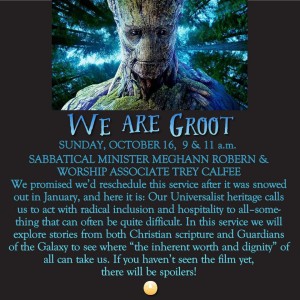

When I was initially working on this sermon, as evidenced by the description of the worship service from January, I thought the focus should be more on our first principle, the inherent worth and dignity of every person. But the more I’ve worked through it, the more I’ve found this story to be about the seventh principle — the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

That’s quite a mouthful. You’d think it could be shorter, you know, maybe just “the interdependent web”. But humans sometimes aren’t that good at recognizing the bigger story, especially when we’re in pain, or mad, or afraid. And us Unitarian Universalists in particular, sometimes we like to believe that we’re exceptional to the point of being set apart from others, removed from the things that we think we’ve rejected or left behind as our tradition has progressed. So we need this big mouthful of a reminder that we are deeply, deeply set into this web of existence, whether it’s moving us to joy or to sorrow.

The interdependent web of all existence. Even the pieces we don’t like.

The interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part. We are intimately, inextricably connected to the people we dislike. Dare I say it, we are inextricable from those we hate.

We are a part of those who we try to shut out and disown as not being us.

This brings me to the reading, often titled “The Faith of the Canaanite woman”. I think it should have a subtitle: “In Which Jesus Is Wrong.”

I love this story. It’s one of the best stories for a perfectionist, overfunctioning person like me who’s spent years learning that mistakes are inevitable, that we are flawed beings always learning how to be better to each other.

And there’s lots of different interpretations of this story in Christian exegesis, and lots of different ways of working the text so that Jesus is still perfect. Perhaps those versions of the story speak to you, and that’s perfectly ok. One of the things I love most about Unitarian Universalism is that not only do we embrace different stories, we embrace different sides of the same story. We say, “Yes, and.”

So this morning, we’re focusing on the idea that Jesus was wrong. He gets called out on it, and instead of doubling down in his wrongness, throwing a tantrum, or any other deflecting behavior, he says, “Oh my gosh, you’re right.” And then he makes amends.

Think about the power dynamics here. A desperate women from an oppressed, systematically maligned population shows up asking for help for her child from a healer. This healer, who knows he could ease this child’s suffering, says, “No, I don’t think so. You’re not the right kind of people. In fact, I’m not sure you’re even a person. You’re like a dog.” (Which, I just want to point out, I know for many in this congregation, is not an insult. But apparently it was for Jesus. That’s another sermon).

And this woman, who has already made herself vulnerable just by showing up and begging for help, doesn’t back down. She says, “Even dogs get scraps from the table.” Even dogs are part of the household.

Even if I’m willing to debase myself to agree with your assessment of me as less than you, I’m still a part of the interdependent web and you should respect that.

I am willing to believe in you and your power to save my child. Why won’t you believe in me?

And there it is. Jesus realizes that he actually knows nothing about her life, or what difficult choices she had to make to survive. He has judged her worth solely on her identity as a Canaanite. He reacts like a bigot.

Now, this is not to say that the Canaanite woman is perfect. We don’t know anything about her, or her past behavior. She could be toxic in any number of ways– but not just because she’s a Canaanite.

And that’s the point of the story — that in this moment, it doesn’t matter. In this moment, right here, she is asking for help for someone she loves from someone she knows can help at no risk or loss to himself. Whatever she may have said or done in her past is irrelevant.

So how does this tie in to Guardians of the Galaxy?

I love genre stories, because they help us get understanding about our own lives by removing us from it. When Nichelle Nichols, who played Uhura on the original Star Trek series, was considering leaving the show, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. asked her to stay on. He told her how important it was for black people, especially young black children, to see themselves on television as something other than a servant. Star Wars tells us a story about the search for identity and resisting imperialism. Superheroes awe us with their powers while teaching us how to process the power of our emotions and actions in the world.

And sometimes, those heroes are anti-heros. The Guardians of the Galaxy are our Canaanites, and unlike the Canaanite woman from our others story, we know all about the history of this motley crew of criminals.

Peter Quill, con man and thief. He was kidnapped from earth as a young boy, after the death of his mother, and maintains emotional distance from those around him as a protection.

Gamora, thief, assassin for hire. Her family was killed in front of her when she was a child, and she was “adopted” by the man who did it. He turned her into a living weapon. She is fighting to both survive and find a way out.

Drax, a man consumed by a need for violent revenge after the slaughter of his family. He solves problems with brute force.

Rocket. He’s a freak, a mistake made from the progress of science without the temper of ethics. He is, more than any of the rest of them, alone in the universe, carrying memories of torture and abuse and living with the constant ridicule and mocking of those around him every day. He is cruel, and angry.

All created by the systems in which they existed. All have had to live for most of their lives with no one validating their inherent worth and dignity, so they are forced to carve it out for themselves, often resorting to brutality, fear, and avoidance rather than right relationship.

And yet, when push comes to shove, when they realize that they can contribute in a meaningful way to the larger community, to the survival of the very people who malign and oppress them, they rise to the occasion.

And then there’s Groot, the giant tree-being. Groot enters this story as Rocket’s muscle, giving him physical and emotional support in a world that created him and then abandoned him. While Groot can only vocalize the words “I am Groot,” he understands everything said to him. Groot becomes the force binding them together, the one among them who can create beauty amongst ugliness.

All of this is important for the moment that made this movie worth a sermon. You have to know how awfully these people have been treated to understand how huge it was for them to join the fight to save the world that had abused them. You have to know how criminal their choices have been to understand the risk they took by contacting the NovaCorps, the military and police forces of the first planet to be attacked.

You have to know how little they think of themselves, how little expect from their lives to understand how shocking it was that Groot sacrificed himself to save them. In that moment, when Groot uses “we” for the first time, he is using his power to heal those he cares about. He is telling them, you showed up, and so you are worth saving.

So where do you find yourself in this story?

Maybe you’re one of this mercenary crew, asking for someone to believe in you, to believe that you can change the world even as it’s trying to tear you down. Maybe you’re one of the NovaCorps, having to decide whether or not to give these people a chance despite their history.

And yes, I know that there are people, that there are relationships, that are so toxic we must, one-on-one, break those ties, for our safety and for the safety of others in our care. I’ve had to do this myself. There are people I will never let back into my life. One person cannot take down a Ronan, bent on destroying everything them just because they can. And people like this do exist.

But these toxic, destructive people remain part of our interdependent web. Even if we can’t be in direct relationship with them, we will always be in indirect relationship with them, and so by pouring love and and kindness out into that interdependent web of all existence, we can support them from a distance. Intimacy is not always required to provide care.

A large, healthy system, like the one this congregation has worked so hard to become, is strong enough to take a risk as a community when the risk is too great for one single person to bear. Like the criminal protagonists and the NovaCorps, we are stronger when we work together to fight a common enemy for the good of all. Like Jesus, we have the power to heal those who come to us, who willingly join with us.

And here’s the really difficult part of the story for us to bring into our daily lives. After the Guardians defeat Ronan, after they save the planet, and stop the spread of destruction to the rest of the universe, NovaCorps erases their criminal records. Builds them a ship to replace the one they lost in the battle. And then lets them go free.

They are given a clean slate, and the chance for a new beginning. The past is forgiven, but not forgotten — there is an understanding that if they break this new covenant, there will be repercussions. But until that happens, they will be treated like any other member of the community. I love this, because it’s not a magical panacea that erases everything about their lives and personalities.

Your past is always a part of who you are. Their personalities have not changed, but now? Now they have a vision of the future in which they are empowered to make better choices, despite the systems of oppression that have formed them. The sequel hasn’t come out yet, so I’m sure we’re going to see some bad choices yet to come. They’re flawed. We’re flawed.

But as the story of the Canaanite woman tells us, even Jesus was flawed. Groot was flawed. We can be flawed and still be powerful beings co-creating the universe, one choice at a time. We can still recognize the respect the ways in which we are connected to one another, from our closest friends and family to strangers on the other side of the globe.

We are Groot.