Listen to the sermon here:

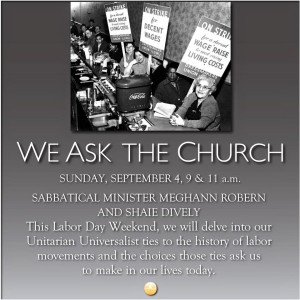

We Ask the Church

Or, watch and listen to the sermon on Facebook

I used to be a screenwriter. Almost ten years ago, the Writers Guild of America went on strike, right when my career was about to take off. I’d sold a project to a big studio AND it was being made, which doesn’t always happen. You’d be surprised how many successful screenwriters there are who’ve never seen something they wrote made into a movie. But they get paid for their work, thanks to the guild.

But because it was my first project, and it had been optioned but not purchased, and production hadn’t started, when the strike began, I was in this sweet spot area of having a lot of industry buzz around my name, but not yet enough “units” to be eligible for guild membership.

And before any of you ask, I’ll only tell the name of my movie to whoever takes the Program Council Chair position.

So one day, while my day job boss was down on the picket line, I get a call from my agent, Howie. Now, I’m sure that many of you have a very particular personality in mind when you think of a Hollywood agent. Howie is an exception. I’m pretty sure if I called him today he’d still talk to me.

So Howie calls me up, and after some checking-in small talk, he gets real quiet. “Meghann,” he says, “are you a member of the guild yet?” I said “No, I’m not eligible until they start production.” Silence. Then he says, “As your agent, you need to know that I can get you work right now.”

And what he’s not saying, what he and I both understand without having to say it, is that not only could I get work, but I could get a lot of work. More than any other fledgling writer could reasonably hope for at this point in their career.

And I had one of those moments that technically only lasts a second or two, but encompasses what feels like decades of thought. I remembered that I grew up with food in my belly and consistent health care because of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists and the American Federation of Musicians. In that one second I recalled all the conversations I’d overheard in recording sessions about scale pay, and how my parents never questioned that someone should be paid fairly.

I thought about my boss, the man who had taken me under his wing, treated me fairly, and given me every opportunity to move into my own career. I remembered that the money I’d already made from this movie was only in my bank account because of this guild that was on strike.

I knew, in that one second, that while I may not be a member on paper, I was a member in spirit.

“I’m sorry, Howie. I can’t cross the picket line. I wouldn’t be able to live with myself.”

“Good girl,” he said. Then he hung up.

And I never worked in Hollywood again.

I tell you this story today because it’s my example of what “labour union” means at a personal, spiritual level and not just politics. UU minister Rev. Aaron McEmrys, who was an organizer before following his call to ministry, describes it perfectly for me. He says,

I choose to use the word, “union”, because it best describes what happens when groups of individuals come together in a spirit of mutual support, respect and love. In this sense, the concept of union is one of the most beautiful and important “spiritual” words in my vocabulary. Whether people are organizing through the “official” mechanisms of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) or through “unsanctioned” means – they are nonetheless organizing themselves into a relationship of “union” with one another, where “an injury to one, is an injury to all.”

Rev. Aaron also teaches UUs about our long history of supporting labour movements in this country. William Ellery Channing, in the 1830s, said that all people had the same “tremendous potential” regardless of economic class, and that the exploitation of workers was denying them their ability to fully manifest that potential. Theodore Parker preached on poverty and its direct ties to abuse of workers. Over a hundred years ago, John Henry Holmes wrote a description of that same link between systemic poverty and worker injustice that could have been written today:

Poverty, in this age as in every age, in our country as in every country, is primarily due to the fact of social injustice – that employment cannot be had by those who are ready to work; that employment even when regular is not paid enough to enable the faithful and efficient workman to guard against illness, to protect his widow from dependence, or to provide for his own old age; that insufficient wages force thousands of families to crowd into unhealthy tenements, to eat insufficient food, and to wear insufficient clothing, thus paving the way for physical weakness and disability; that accidents rob the wage earners without compensation from society; that taxes are inequitable, throwing the chief burden upon the poor instead of upon the rich; that natural resources, which are the basis of all wealth, are in the hands of a few instead of under the control of society at large, and are thus exploited for the benefit of the few and not for the sake of the common welfare; that the distribution of wealth is grossly unfair and disproportionate – in the final analysis, that society is organized upon a basis of injustice and not of justice, and is permeated by the spirit of selfishness and not of love. (The Revolutionary Function of the Modern Church (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1912) pp. 100-101)

Heartbreaking words, because they still ring so true. And yet. Hearing it so perfectly summed up, it becomes so thick and dense that I am overwhelmed by the magnitude of it. How am I, one person, supposed to help, especially when I’m as tied up in it as everyone else?

After the writers guild strike came the economic crash. My boss had to let me go. I had a new baby, a house I couldn’t sell, and I couldn’t find a job to save my life. Eventually my unemployment insurance ran out. And I know, without a doubt, that we would have ended up homeless, with Prudence in foster care, if it weren’t for our family’s economic privilege.

We had people not only willing, but also ABLE to support us in a time of great need. My family of musicians union members now included Josh’s family of teacher unions. Once again, my life, and the life of my child, was sustained by the ongoing work of the labour movement.

Even finally following my lifelong call to ministry — the years of seminary, moving here to serve as your intern minister last year– was only possible because of the economic privilege given to me — GIVEN to me, not earned by me — by union workers.

The quote I chose for the order of service today is also from Cesar Chavez, one of the co-founders of National Farm Workers Association. A devoted Catholic, he specifically reached out to religious communities for support, asking them “to sacrifice with the people for social change, for justice, and for love of [sibling]. We don’t ask for words. We ask for deeds. We don’t ask for paternalism. We ask for servanthood.”

And yet, I know that fear that tells us to cross picket lines — fear of hunger, fear of losing our children, fear of homelessness. I know some of you here in this sanctuary are not just living with these fears as a possible future but are also living the reality of not knowing where next week’s food will come from, or where you’ll be sleeping.

I also know the fear of activism. I’ve thought about what I want displayed on the back of my car, and whether it will bring violence to me and my family. I’ve stayed out of protest situations wherein I felt the risk to my safety was too high. And I reconsider those decisions every day. I carry guilt for those decisions every day. I know that the fact I even have a choice is deeply rooted in my privilege. I’m not sure I’m as brave as Shaie’s mom, or as many of you here today.

But what I do know is that the more of people’s stories I hear, the more I know about people’s lived experience, the braver I become. Bravery doesn’t mean the fear goes away — it means going ahead even when we’re afraid. So let’s continue to listen to people’s stories, and to make safe space for those stories yet untold.

I also know that when I’m faced with a task that feels overwhelming, insurmountable, I have to find a way to make it smaller. I break it down, into little pieces, that I can conquer one at a time. And this is where our choices come in.

This is where solidarity, where Cesar Chavez’s call to servanthood and deeds looks like joining a boycott instead of joining the front lines of the protest itself. Where Shaie’s mom did as much to support the farm workers by telling their story to her daughter as she did by putting that bumper sticker on her car.

We cannot live into affirming the worth and dignity of every person and the interdependent web, two of our seven Unitarian Universalist principles, if we cannot stomach the reality of where our fruit comes from.

We cannot claim that we believe Black Lives Matter if we don’t see how Black Lives are forced into poverty through unfair labour practices.

We cannot venerate the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as a civil rights leader if we ignore his call that workers’ rights are civil rights.

So how is each of us willing to live up to this call?

What choices do we make, every day, no matter how small, that bend the arc of the universe towards justice?

How can we deepen our relationships with those around us, to strengthen the web that holds us in love?